|

The final frontier. In a desolate place not far from

Tombstone, Arizona is a robot telescope from the University of Iowa which

was constructed and is operated under the guidance of Robert Mutel, a

professor at our university. The building which houses the telescope is

shown in Figure 26 [below, left]. The roof of this building rolls to the

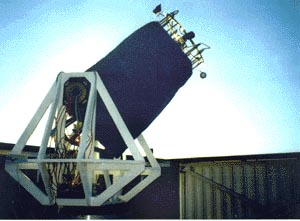

left to allow the telescope to view the sky. This telescope, the Iowa

Robotic Telescope (IRO), is seen in the photograph of Figure 27 [below,

right]. It is a matter of great coincidence, and perhaps of irony, that

this telescope can play a crucial role in the final confirmations of the

small comets.

This will not be the first search of the sky for small comets with a

ground-based telescope. About 10 years ago Clayne Yeates, a scientist at

the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California designed a very

clever way of detecting the small comets with the Spacewatch Telescope of

the University of Arizona. His method relied upon passage of small comets

by the Earth in an organized stream as inferred from the motions of

atmospheric holes observed with Dynamics Explorer 1. Clayne, like so many

other scientists in the 1980s, did not believe that the small comets

existed. His technique to detect these small, dark, fast objects is

shown in Figure 28 [left]. Telescopes are traditionally pointed so that

they are staring at the stars. In order to see the small comets Clayne

used the telescope in a "skeet shooting" manner. In other

words, the telescope's pointing was moved in such a way as to keep the

small comets in the sights of the telescope for a sufficiently long time

that they would be recorded in the images.

clever way of detecting the small comets with the Spacewatch Telescope of

the University of Arizona. His method relied upon passage of small comets

by the Earth in an organized stream as inferred from the motions of

atmospheric holes observed with Dynamics Explorer 1. Clayne, like so many

other scientists in the 1980s, did not believe that the small comets

existed. His technique to detect these small, dark, fast objects is

shown in Figure 28 [left]. Telescopes are traditionally pointed so that

they are staring at the stars. In order to see the small comets Clayne

used the telescope in a "skeet shooting" manner. In other

words, the telescope's pointing was moved in such a way as to keep the

small comets in the sights of the telescope for a sufficiently long time

that they would be recorded in the images.

To Clayne's surprise he in fact did find the small comets in his images

and in numbers that were predicted from the observations of atmospheric

holes. The small comets were clearly detected in the images. Astronomers

insisted that the comets should be detected in two consecutive

photographs. Clayne returned to the telescope and gained these pairs of

images of each small comet. Astronomers returned with the ridiculous

demand that they now needed three images. The small comets were there and

the astronomers of the Spacewatch Telescope could only offer the now

familiar "camera noise" as a defense. Because of his untimely

death Clayne was not able to continue his brilliant applications of

ground-based telescopes in the pursuit of small comets.

The Iowa telescope is now being used to verify the existence of the small

comets. The initial images already are being carefully scrutinized. In

order to prevent any further claims of "camera noise" the image

of a small comet is taken with two exposures in the same picture. This

simple method is shown in Figure 29 [right]. The small comet is moving in

the telescope's view. A CCD sensor is placed at the focus of the

telescope in order to record the image. These sensors are found in many

of the present-day video cameras although the sensor in the Iowa

telescope has some special design features. In order to distinguish a

real comet signal from "camera noise" two exposures are taken

with a mechanical shutter. One of the exposures is twice as long as the

other and these exposures are separated by a shutter closed time equal to

the short exposure time. The result for detection of a single small comet

is two trails, one about twice as long as the other and separated by a

gap with no trail. This is shown in the lower part of Figure 29. The

ratios are not quite exact because of the small blurring due to the

telescope's resolution. Also you will note that the trails are shown as

dark, rather than bright trails. This inversion of dark and bright is

done because the human eye can detect the events more easily in the

images.

order to prevent any further claims of "camera noise" the image

of a small comet is taken with two exposures in the same picture. This

simple method is shown in Figure 29 [right]. The small comet is moving in

the telescope's view. A CCD sensor is placed at the focus of the

telescope in order to record the image. These sensors are found in many

of the present-day video cameras although the sensor in the Iowa

telescope has some special design features. In order to distinguish a

real comet signal from "camera noise" two exposures are taken

with a mechanical shutter. One of the exposures is twice as long as the

other and these exposures are separated by a shutter closed time equal to

the short exposure time. The result for detection of a single small comet

is two trails, one about twice as long as the other and separated by a

gap with no trail. This is shown in the lower part of Figure 29. The

ratios are not quite exact because of the small blurring due to the

telescope's resolution. Also you will note that the trails are shown as

dark, rather than bright trails. This inversion of dark and bright is

done because the human eye can detect the events more easily in the

images.

An early candidate image of a small comet which was taken on October 19,

1998 is shown in Figure 30 [right]. The mottled appearance of the image

is indeed due to camera noise. This picture is presented in order to

provide the reader with an accurate accounting of the difficulties in

detecting the presence of these small dark comets, and the reasons why

these objects were not previously discovered by accident with

ground-based telescopes. At the lower border of the photograph is the

dark trail of a star. In the center of the image are the two trails of a

single small comet.

An early candidate image of a small comet which was taken on October 19,

1998 is shown in Figure 30 [right]. The mottled appearance of the image

is indeed due to camera noise. This picture is presented in order to

provide the reader with an accurate accounting of the difficulties in

detecting the presence of these small dark comets, and the reasons why

these objects were not previously discovered by accident with

ground-based telescopes. At the lower border of the photograph is the

dark trail of a star. In the center of the image are the two trails of a

single small comet.

The analysis of the image proceeds by verifying that the trails conform

to the very demanding restraints. The results of the analysis are shown

in Figure 31 [left]. It is very exciting to find the trails recorded by

more than 200 individual photoelectric eyes, or "picture

elements", of the CCD conform to the expectations from the special

shutter operation. It would take billions of such pictures before a

"noise event" of this type would occur. We are well on our way

for the final confirmation of the existence of small comets. A large

number of such detections is necessary to complete the confirmation.

elements", of the CCD conform to the expectations from the special

shutter operation. It would take billions of such pictures before a

"noise event" of this type would occur. We are well on our way

for the final confirmation of the existence of small comets. A large

number of such detections is necessary to complete the confirmation.

Closing comments. I would like to note that it seems almost

incredible that two scientists, John Sigwarth and myself, from the

University of Iowa have participated in the four major milestones in the

discovery of small comets. Briefly these milestones are as

follows.

|

1986

|

Initial detection of small comet impacts into the atmosphere

with the Iowa camera on Dynamics Explorer 1

|

|

1989

|

Direct sightings of small comets with the Spacewatch Telescope

of the University of Arizona

|

|

1997

|

Confirmation of atmospheric impacts and discovery of

disrupting comets with the Iowa cameras on the Polar spacecraft

|

|

1999

|

Current search for small comets with the Iowa Robotic

Observatory in Arizona

|

The scientific debate concerning the existence of small comets has been

characterized by intense intellectual and emotional turmoil. I often

recall the droll statement attributed to the famous physicist Max Planck

who had also experienced considerable criticism from his colleagues.

[Next Page]

"Scientists don't change their minds,

they just die."

|

clever way of detecting the small comets with the Spacewatch Telescope of

the University of Arizona. His method relied upon passage of small comets

by the Earth in an organized stream as inferred from the motions of

atmospheric holes observed with Dynamics Explorer 1. Clayne, like so many

other scientists in the 1980s, did not believe that the small comets

existed. His technique to detect these small, dark, fast objects is

shown in Figure 28 [left]. Telescopes are traditionally pointed so that

they are staring at the stars. In order to see the small comets Clayne

used the telescope in a "skeet shooting" manner. In other

words, the telescope's pointing was moved in such a way as to keep the

small comets in the sights of the telescope for a sufficiently long time

that they would be recorded in the images.

clever way of detecting the small comets with the Spacewatch Telescope of

the University of Arizona. His method relied upon passage of small comets

by the Earth in an organized stream as inferred from the motions of

atmospheric holes observed with Dynamics Explorer 1. Clayne, like so many

other scientists in the 1980s, did not believe that the small comets

existed. His technique to detect these small, dark, fast objects is

shown in Figure 28 [left]. Telescopes are traditionally pointed so that

they are staring at the stars. In order to see the small comets Clayne

used the telescope in a "skeet shooting" manner. In other

words, the telescope's pointing was moved in such a way as to keep the

small comets in the sights of the telescope for a sufficiently long time

that they would be recorded in the images.

order to prevent any further claims of "camera noise" the image

of a small comet is taken with two exposures in the same picture. This

simple method is shown in Figure 29 [right]. The small comet is moving in

the telescope's view. A CCD sensor is placed at the focus of the

telescope in order to record the image. These sensors are found in many

of the present-day video cameras although the sensor in the Iowa

telescope has some special design features. In order to distinguish a

real comet signal from "camera noise" two exposures are taken

with a mechanical shutter. One of the exposures is twice as long as the

other and these exposures are separated by a shutter closed time equal to

the short exposure time. The result for detection of a single small comet

is two trails, one about twice as long as the other and separated by a

gap with no trail. This is shown in the lower part of Figure 29. The

ratios are not quite exact because of the small blurring due to the

telescope's resolution. Also you will note that the trails are shown as

dark, rather than bright trails. This inversion of dark and bright is

done because the human eye can detect the events more easily in the

images.

order to prevent any further claims of "camera noise" the image

of a small comet is taken with two exposures in the same picture. This

simple method is shown in Figure 29 [right]. The small comet is moving in

the telescope's view. A CCD sensor is placed at the focus of the

telescope in order to record the image. These sensors are found in many

of the present-day video cameras although the sensor in the Iowa

telescope has some special design features. In order to distinguish a

real comet signal from "camera noise" two exposures are taken

with a mechanical shutter. One of the exposures is twice as long as the

other and these exposures are separated by a shutter closed time equal to

the short exposure time. The result for detection of a single small comet

is two trails, one about twice as long as the other and separated by a

gap with no trail. This is shown in the lower part of Figure 29. The

ratios are not quite exact because of the small blurring due to the

telescope's resolution. Also you will note that the trails are shown as

dark, rather than bright trails. This inversion of dark and bright is

done because the human eye can detect the events more easily in the

images.

An early candidate image of a small comet which was taken on October 19,

1998 is shown in Figure 30 [right]. The mottled appearance of the image

is indeed due to camera noise. This picture is presented in order to

provide the reader with an accurate accounting of the difficulties in

detecting the presence of these small dark comets, and the reasons why

these objects were not previously discovered by accident with

ground-based telescopes. At the lower border of the photograph is the

dark trail of a star. In the center of the image are the two trails of a

single small comet.

An early candidate image of a small comet which was taken on October 19,

1998 is shown in Figure 30 [right]. The mottled appearance of the image

is indeed due to camera noise. This picture is presented in order to

provide the reader with an accurate accounting of the difficulties in

detecting the presence of these small dark comets, and the reasons why

these objects were not previously discovered by accident with

ground-based telescopes. At the lower border of the photograph is the

dark trail of a star. In the center of the image are the two trails of a

single small comet.

elements", of the CCD conform to the expectations from the special

shutter operation. It would take billions of such pictures before a

"noise event" of this type would occur. We are well on our way

for the final confirmation of the existence of small comets. A large

number of such detections is necessary to complete the confirmation.

elements", of the CCD conform to the expectations from the special

shutter operation. It would take billions of such pictures before a

"noise event" of this type would occur. We are well on our way

for the final confirmation of the existence of small comets. A large

number of such detections is necessary to complete the confirmation.